By Hira Azher (she/her), Communications Coordinator

On July 26, 2025, we will celebrate the 35th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This crucial piece of disability rights legislation would not have been possible without the decades of disability advocacy that came before it.

Section 504 Sit-Ins

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities in federally-funded activities and programs. Section 504 was passed in 1973, but was not really enforced. On April 4th, 1977, after the government refused to sign the 504 regulations into law, protests occurred across the nation.

One of the most prominent protests took place in San Francisco. 120 activists occupied San Francisco’s Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) Federal Building. Government officials attempted to remove the activists by cutting the phone lines and restricting food and water, but the activists were prepared. Several community organizations, including the Black Panther Party, showed up and provided support for the disability activists. After 28 days of the Sit-in and consistent pressure from the protestors, the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare finally agreed to sign and implement Section 504.

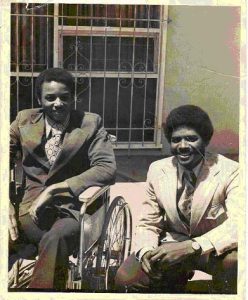

Image of Brad Lomax (left) and his brother, Glen Lomax (right).

One of the leaders of the San Francisco 504 Sit-in was Brad Lomax. Brad Lomax was a disabled Black man and a member of the Black Panthers. He built alliances between the disability and civil rights communities which were crucial for the Sit-in’s success, as the Black Panther Party ensured the disability rights activists received hot food, water, and other supplies.

Disability in Schools

In 1975, Congress passed the Education for Handicapped Children’s Act, later renamed as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 1990. This law was spurred by the same zealous disability advocacy that ensured regulation of Section 504. This Act required all public schools that accepted federal funds to provide equal access to education and at least one daily free meal to children with disabilities.

This Act met four major goals:

-

Ensured special education services are available to children who need them

-

Guaranteed that decisions about services for students with disabilities are fair and appropriate, including placing them in the least restrictive environment

-

Established specific managing/auditing requirements for special education

-

Provided federal funds to help states educate students with disabilities

Building Intersectional Alliances

During the 1980s, there was long battle over the Civil Rights Restoration Act (CRRA). The CRRA was tasked with overturning Grove City College v Bell, a Supreme Court decision that had significantly restricted the reach of all of the Section 504 statutes that prohibited race, ethnic origin, gender, or disability discrimination by recipients of federal funds. For the first time ever, the disability community worked in leadership roles with representatives of other marginalized groups to get a major piece of legislation passed.

In coalition again in 1988, the civil rights and disability communities amended the Fair Housing Act (FHA). These changes required improved enforcement mechanisms of the Act and the addition of disability anti-discrimination provisions. This was the first time disability anti-discrimination provisions were included in a traditional civil rights statute banning racial discrimination. Through collective work on the CRRA and FHA, the disability community formed deep alliances with the civil rights community and other marginalized groups. These alliances became crucial in the fight for the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Legal Battles

In the 1980s, multiple Supreme Court decisions began to limit how and when Section 504 could be applied. One major hurdle was the Supreme Court case of Southeastern Community College v. Davis. In this case, Frances Davis applied to the nursing program at Southeastern Community College, a school that received federal funds. Davis had a hearing disability that required her to lip-read. The College denied Davis’s application on the basis that her disability would not allow her to meet the nursing program’s requirements. After asking for reconsideration, her application was denied again. The Supreme Court upheld Southeastern Community College’s decision, thereby allowing federally-funded entities to legally discriminate against people with disabilities.

Following this case, the disability rights community jumped into action and focused on re-educating the Supreme Court. Their goals were achieved in the landmark case, Consolidated Rail Corporation v. Darrone. In this case, Darrone was a locomotive engineer for Consolidated Rail Corporation. Following an accident, in which Darrone’s left hand and forearm were amputated, the Corporation refused to re-employ him. Since Consolidated Rail Corporation had received federal funding for worker retraining and termination allowances, they were required to abide by the anti-discrimination provisions in Section 504. The Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund filed an amicus brief on behalf of 63 disability rights organizations and their joint advocacy was successful. This case proved employment discrimination was not allowed under Section 504, and these regulations later became part of the ADA.

The disability community continued their legal advocacy through several landmark cases, such as School Board of Nassau County v. Arline, which proved people with AIDS and other illnesses were covered under Section 504, and later, the ADA. These legislative victories showcased the community’s legal, organizing, and negotiations skills; and formed the congressional relationships that were necessary in passing the ADA.

Capitol Crawl

Spurred by a draft bill prepared by the National Council on Disability, the ADA was introduced to Congress in 1988. The ADA was revised and passed by the Senate in 1989, but the process was slow and several months went by without any action from Congress. In response, over 1,000 protesters came to Washington D.C. on March 12, 1990 to urge Congress to approve the law. Part of this demonstration, included the Capitol Crawl, in which more than 60 activists abandoned their mobility aids and crawled up the 83 stone steps that lead to the Capitol building. Among these activists was Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins, an 8-year-old girl with cerebral palsy who declared “I’ll take all night if I have to” as she pulled herself up the steps. The Capitol Crawl was a direct physical demonstration of how inaccessible architecture impacts people with disabilities; and is cited as one of the most important catalysts in passing the ADA. A few months later, on July 26, 1990, the ADA was signed into law.

The ADA today

The passage of the ADA was a milestone in the disability rights movement, but it is not the end. It is our duty to continue the legacy of the zealous activists before us by continuing to fight for disability justice. Now, when disabled people are described as “epidemics destroying families;” when 40% of the Administration for Community Living (ACL) staff is cut; and when the entire protection and advocacy system is under threat; it is imperative that we organize, build alliances, and fight back.

Image of Hira. Hira is a young, Pakistani woman with curly black and red hair. She is smiling at the camera, wearing a white shirt and blue denim jacket. Hira is posed at a table in front of a river and several skyscraper buildings.

Hira Azher (she/her) is the Communications Coordinator at the disAbility Law Center of Virginia. She is a fierce advocate for disability justice and is particularly interested in mental health advocacy and the Mad Movement. At dLCV, she works to create inclusive and accessible communications. Outside of work, she enjoys reading and playing with (or probably annoying) her two cats.

dLCV Blog Content Statement: dLCV is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides information and referral, legal representation, technical assistance, short-term assistance, systemic advocacy, monitoring and training to Virginians with disabilities. Our services are provided free of charge. We are independent from state and local government.

The statements given by staff or volunteers for our blog content are NOT intended to be taken as legal advice. Instead, our blog content aims to focus on the lived experiences of people with disabilities and shine a light on the diverse perspectives within Virginia’s vibrant disability community.